November is the month of remembrance. A time to remember the men and women who have given their lives for their country, protecting their loved ones. Soldiers on the front line in many wars both in years gone by and sadly far too recently. Also not to be forgotten are the people left at home to keep both the country and homes running during these times of conflict.

Our feature looks at the Battle of the Somme – 141 days ending 100 years ago this month, of what can be said was the bloodiest battle of World War One, with such appalling casualty figures symbolising the abject horrors of trench warfare.

The start of the battle

The main aim of the battle was to relieve the French Army who were fighting at Verdun, whilst weakening the German forces. The French were taking severe losses to the east of Paris so the Allied High Command decided that if they attacked the Germans to the north of Verdun it would pull some of their forces away from the French. So, on the 1st July 1916, the Battle of the Somme began.

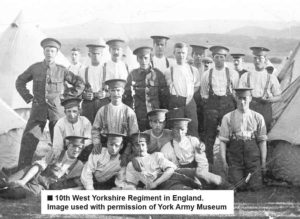

One major problem was that many of the men were part of ‘Kitchener’s Volunteer Army’ and therefore had no real idea of what warfare entailed. Some soldiers were just boys as young as 16 who had been persuaded to volunteer by the posters as a way of showing their patriotism. The British soldiers were therefore at a huge disadvantage as they were not prepared or trained for the battlefield.

The military thinking and strategic planning was somewhat behind the times too. For example, the British had put a regiment of cavalry on standby intended to exploit the damage done by the infantry attack. The previous two years of warfare would have surely shown that cavalry were no longer viable but the British military were still placing faith in them. However, despite doubt by both several British commanders as well as General Foch, head of the French Army that the attack in the Somme would achieve anything, the orders were given from London.

The battle began with seven days of artillery bombardment before the infantry were sent in. 1,738,000 shells were fired at the Germans to destroy their trenches and the barbed wire. Field Marshall Haig said “The enemy’s position to be attacked was of a very considerable character, situated on high, undulating tract of ground. They had deep trenches, bomb proof shelters, wire entanglements forty yards broad often as thick as a man’s finger. Defences of this nature could only be attacked with the prospect of success after careful artillery preparation.”

This didn’t work though. As the artillery fell silent, the men were sent over the top. The Germans had weathered the bombardment quite safely in deep dugouts, and when this stopped, they knew it would be the signal for infantry to advance.

As the soldiers advanced over a 25 mile front they were mown down by machine gun and rifle fire. In total, 19,240 poor British men and boys lost their lives with countless more injured making it the bloodiest day in the history of the British army.

Despite taking just three square miles of territory that day, the British decided to press their advance. The media reporting back home was less than accurate too as reports were scrutinised by the government before publication, and journalists only had information given to them by the military. One report from the Daily Chronicle published on July 3rd says “At about 7.30 o’clock this morning a vigorous attack was launched by the British Army. The front extends over some 20 miles north of the Somme. The assault was preceded by a terrific bombardment, lasting about an hour and a half. It is too early to as yet give anything but the barest particulars, as the fighting is developing in intensity, but the British troops have already occupied the German front line. Many prisoners have already fallen into our hands, and as far as can be ascertained our casualties have not been too heavy.”

Even though parents, wives and children were kept in the dark at home by the reporting, those on the front line knew the horrors only too well. George Coppard, a machine gunner wrote “The next morning (July 2nd) we gunners surveyed the dreadful scene in front of us. It became clear that the Germans always had a commanding view of No Man’s Land. The British attack had been brutally repulsed. Hundreds of dead were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high water-mark. Quite as many died on the enemy wire as on the ground, like fish caught in the net. They hung there in grotesque postures. Some looked as if they were praying; they had died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall. Machine gun fire had done its terrible work.”

Pals Battalions

Although the press was doing a great job of reporting positively, as the casualty lists began to appear in the second week of July the toll of the battle became apparent. The towns which provided the Pal’s Battalions were the hardest hit. The Leeds Pals, the 15th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment, suffered greatly losing a total of 248 men. It was reported at the time that there was not a street in Leeds that didn’t have at least one house with curtains closed in mourning.

The 11th East Lancashire battalion – the Accrington Pals suffered even more losses. Of the 720 men who went into action on that first day, 584 of them became casualties.

The Pals had been put together after the government realised more civilians would be prepared to volunteer if they could be assured of serving alongside people they knew. After starting the scheme in London, it soon spread until cities and businesses were competing to provide the biggest number of recruits. As the Pals battalions trained and deployed together it provided a powerful unifying and motivational force. This kept the men fighting as the realities of war set in, but the men who had lived and worked together in their communities were now dying together.

It was estimated that by the end of the war men from up to 16000 villages had volunteered. A journalist in the 1930’s sought to find ‘thankful’ villages – those communities who had not lost a single man in the war. Estimates suggest there were just 53 that could claim that title.

The Battle Continues

Following that first deadly day, the battle continued apace. Despite cavalry becoming increasingly redundant in warfare, horses played a vital role in moving supplies and men. On the 14th July though, two regiments of the 2nd Indian Cavalry Division were sent into action during a surprise dawn attack in the northern part of the Somme. The Germans were taken by surprise as 22000 British troops attacked in the early hours including the cavalry. This was an early victory for Britain as they managed to advance 6000 yards and occupy Longueval village. The cavalry however, failed to take High Wood which remained in German hands.

On the 15th July at the southern end of the British line, Delville wood (known as ‘Devil’s wood’ to the poor men who fought there) was occupied by 3000 soldiers of the 1st South African brigade. The Germans unleashed fierce attacks but the South Africans held on, even as terrible weather turned the wood into a muddy grave. By the time they were relieved five days later only 143 men of the 3000 were left standing.

Towards the end of July, the British troops were also reinforced by the First Anzac Corps, with three Australian divisions of mainly inexperienced volunteers. Anzac officer Aubrey Wiltshire described the Battle of Pozieres which took place on the 23rd July “Shells were screaming around us and machine guns kept flicking, but I had to halt the whole column several times on account of the fatigue of the men.”

In August, the War Office released a public information film for the home front entitled ‘The Battle of the Somme’ which featured real footage from the war. The most powerful scene though of British soldiers going over the top to face the Germans was reconstructed behind the lines. By the autumn, nearly half of the entire UK population had seen the film at the cinema and it broke box office records. The film had a massive impact on the public, who having seen the horror of it for the first time were now even more determined to see the conflict through to the end.

August also saw the Germans losing ground. Morale was low and they had suffered around 250,000 casualties. The Allied naval forces were also blockading the North and Adriatic Seas causing food shortages in Germany.

New Technology Arrives in Autumn

By early September, significant gains had been made by the French and General Haig was under increasing pressure to launch a major attack. On the 15th of the month, Britain unleashed her secret weapon upon the Germans – the Mark I tank. Aided by 48 tanks, 12 divisions of men advanced about a mile and a half, finally taking High Wood. Of the 48 tanks only 21 of them made it to the front line as many of them broke down. Having reached High Wood, the soldiers were exhausted and could not progress any further. That day they sustained 29,000 casualties.

The Germans had new technology of their own – new planes. Having previously dominated the skies, the Allies could no longer compete with the Germans in the air as they deployed the Fokker DII, the Halberstadt and the Albatros DI and DII. This hampered Britain’s observation and artillery targeting.

At the end of September, the British made two substantial gains by taking Morval and Thiepval Ridge. They had mastered the ‘creeping barrage’, an important tactic where artillery was fired just in front of the advancing infantry. As the British 18th Division captured Thiepval fortress village, the Germans put their new planes to good use strafing the trenches. The British troops had to dig in at the nearby network of German trenches.

The autumn also brought with it the wet weather. Exhausted soldiers futilely struggled in a muddy battlefield at the Battle of Le Transloy Ridge on the 1st October. For three weeks the men were under heavy artillery fire, with German planes dropping bombs as they attempted to capture the German trenches. The bad weather hindered further the British air observation and another 57,000 men were killed or injured for the gain of very little ground.

A YORKSHIRE SOLDIER’S DIARY

One Yorkshire soldier, Second Lieutenant Eric Hall who was at the Battle of Le Transloy documented the harrowing times in his diary. On the 20th October he wrote ‘One of the worst days of my life. Was out in mud and pouring rain, sopping wet through all day, stretcher bearing. The casualties during and after the attack on the 18th October were very heavy. Lieutenants Aitcheson, Cain and Elton were killed, Sergeant Major Rideout is missing and amongst the wounded are Lieutenants Gilman, Rutherford, Gravely and Graham. Lieutenant Todd had shell shock and Captain Cudden and Lieutenant Baxter had to go away ill.’ (Extracts from Eric Hall’s diary have been published online by the National Army Museum and can be read by visiting

www.nam.ac.uk/ww1)

The Bloody Battle Finally Comes to an End

The growing casualty lists greatly tested the resolve of the people back home to see the war through. Shrines began to appear on street corners – simple handmade wooden tablets inscribed with the names of the fallen and decorated with crosses were made by communities mourning their losses. This marked the beginning of the collective commemoration that swept the nation in the aftermath of the Great War.

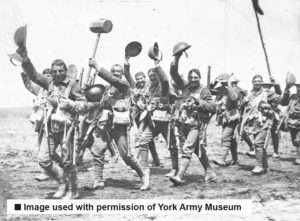

The 13th of November was the last battle on the Somme – at the River Ancre. British troops successfully stormed German defences by again deploying the successful ‘creeping barrage’. Beaumont Hamel and Beaucourt were both taken and 7000 German prisoners were captured.

As the winter weather set in, the fighting was suspended with Haig resolving to resume the offensive after winter. However, in March 1917 the Germans made a strategic retreat to the Hindenburg line rather than face the resumption of the Battle of the Somme.

In those terrible 141 days, the British had advanced just seven miles and failed to break the German defence. By the end of the battle, the British had lost 420,000 men, the French 200,000 men and the Germans 500,000. 51 Victoria Crosses were won by British soldiers including George Sanders from the Leeds Rifles.

World War I finally ended in November 1918 with men returning home just expected to fit back into daily family life and ‘get on with it’, despite the horrors they had been witness to. Unfortunately, as we know, another huge war was soon to follow, with many since, causing devastation to individuals, families and countries. Too many men, women and children lose their lives in the name of war.

In November We Remember.

To learn more about the Battle of the Somme, the First World War and other global conflicts visit Imperial War Museum North in Trafford. The museum is open daily from 10am – 4.30pm and entry to the Main Exhibition Space is free. Visit iwm.org.uk.

The last of a series of specialist talks on the Battle of the Somme will take place at IWM North on November 28 at 3.15pm, detailing the famous names who fought in the battle. These stories are among millions which are being remembered on

www.livesofthefirstworldwar.org, IWM’s permanent digital memorial.